This city park is bounded by East Arrellaga, Garden, East Micheltorena, and Santa Barbara streets. Dedicated in 1980, the park occupies a site with a long and most interesting history.

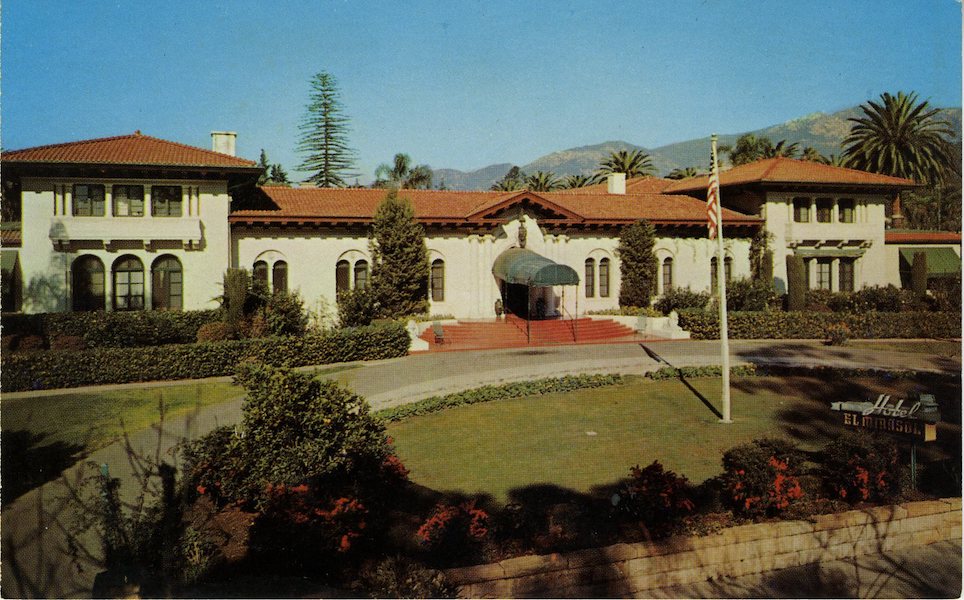

In 1904, Mary Herter bought this block with the intention of having a home built. She enlisted her son, Albert, and his wife, Adele, to help decorate the large Mission Revival style home. Both were artists and they helped transform the home into a showplace, filled with magnificent murals, tapestries, and other artistic pieces. Albert inherited the house in 1913 upon his mother’s death. He decided to turn it into a hotel and christened it, El Mirasol (The Sunflower). The Herters added a series of bungalows to the property and El Mirasol became a destination resort for the wealthy.

In 1920, Herter sold El Mirasol to Frederick Clift, the famous San Francisco hotelier, who continued the tradition of elegance. The Clift family owned the hotel for some 20 years and after that it passed through a number of owners’ hands. By the late 1960s, El Mirasol was primarily a residence hotel and beginning to show signs of age.

The hotel began a new, contentious, chapter in its history in 1966. The hotel suffered two fires that year, which destroyed the west wing of the main building. In the eyes of the hotel’s owner, Jacob Seldowitz, the hotel was beyond salvage. He wished to tear down El Mirasol and replace it with a nine-story hotel which would include a restaurant and a theater. This proposal stirred considerable public debate. For some, it was a wonderful opportunity to give the city’s economy a healthy shot in the arm. For others, the idea of razing the historic El Mirasol and replacing it with a “high-rise” was anathema. For months debates raged over zoning questions, the historic character of the city, impacts on scenic views.

Late in 1967, Seldowitz won a partial victory. His plan for a new hotel was turned down, but he was given permission to tear down El Mirasol. A new battle flared when the El Mirasol Investment Company proposed construction of two 9-story condominium towers on the site. When the city council initially approved the project, opponents appealed to the courts. In July 1969, the court ruled that the city council, by approving the project, had violated the city’s general plan. The towers were out. Eventually, an amendment to the city charter was passed which put a limit on building heights.

But what to do with the site? In 1975, an anonymous donor bought the property and gave it to the city for a park. The name of this benefactor was revealed two years later – Alice Keck Park. Upon her death, she left some $20 million to various Santa Barbara agencies and causes. There was a problem, however. There apparently was a secret, second husband whom Alice never discussed and who could lay claim to a sizeable portion of the estate.

An extensive investigation turned up one Bruno Leonarduzzi, living in Italy. He swore the two had indeed been husband and wife, although irrefutable evidence was lacking. Nevertheless, a settlement was reached, with Leonarduzzi receiving $5 million. One year later Alice Keck Park Memorial Gardens became a reality.

This article originally appeared in the Santa Barbara Independent.